Ross Bradshaw, activist, publisher and writer, was recently invited to Haarlem in The Netherlands to speak about radical bookselling. He knows his trade, which is why Nottingham’s Five Leaves Bookshop, which he founded in 2013, was named Independent Bookshop of the Year at the 2018 British Book Awards. The following article was the basis for the talk that he gave.

Changing the world, one book at a time

by Ross Bradshaw

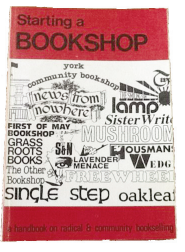

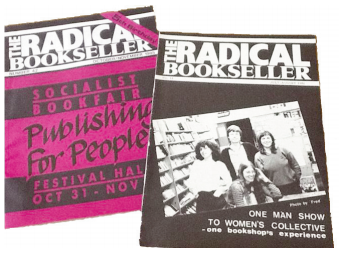

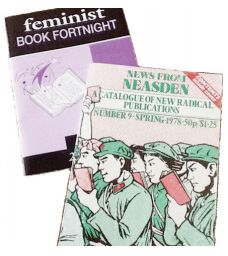

In 1984, the Federation of Radical Booksellers published Starting a Bookshop: a handbook on radical & community bookselling. The radical booktrade in Britain was in its pomp, with its own regular printed journal, The Radical Bookseller, and a reviews journal, News from Neasden. The book exuded confidence. The cover featured logos of bookshops across the country — York Community Bookshop, SisterWrite, First of May Bookshop, Lavender Menace (surely the best bookshop name ever), Oakleaf, The Other Bookshop, Single Step, The Smiling Sun, Mushroom, Lamp, Bookmarks … One chapter missing from an otherwise detailed book was on how to close a bookshop. All the shops and distributors on the cover would come to that point, save for Housmans and Bookmarks of London and News from Nowhere in Liverpool, the great survivors.

Six years later, I wrote an article in Tribune, at the time a weekly Labour Movement newspaper, expressing concern about the number of bookshop closures, caused by political defeats of the Left during the 1980s, and radical territory having been coopted by the main chain, Waterstones, selling feminist and environmentalist books. I reported some bookshops having difficulty recruiting staff due to low pay for a job involving long hours, poor conditions and weekend working. There were some shops doing well, particularly those which had moved on from being the pole of attraction for ‘a few lefties who have been buying obscure Trotskyist or anarchist material in dowdy premises for years might find it difficult to understand why bookshops had sold out by having carpets and books that people actually want to read’. The remaining bookshops were leaving behind the ‘assorted whiffs of squalor and selfrighteousness’ and widening their stock and reach.

In 1982, The Other Branch from Leamington had celebrated some of the squalor of their earlier years: ‘Gradually the hand knitted dolls got mixed up with Marx and Lenin … the kids stole our takings … the tatty wire display rack changed daily according to the ideology of the volunteer on the rota. Later additions to this confusion were live (and on a hot summer’s day, dead) newts for sale, and all the late 60s paraphernalia of king size cigarette papers, pipes, ginseng. The “image” of the shop was completed by two dark, never cleaned windows full of Legalise Cannabis stickers.’ Despite this, books were sold in quantity. The Other Branch’s all time best sellers were:

The Herb Book

The Golden Notebook (novel by Doris Lessing)

The Bean Book

The Massage Book

Protest and Survive

The Very Hungry Caterpillar (children’s)

Woman on the Edge of Time (Marge Piercy)

The Prophet (crap mysticism)

Guide to Growing Marijuana in the British Isles

Guide to Psilocybin Mushrooms

The previous year, Days of Hope in Newcastle printed their best seller list:

Protest and Survive Arguments for Socialism

Spare Rib (feminist) Diary

Woman on the Edge of Time

Marx for Beginners

Inglan is a Bitch (Black liberation

poetry)

Towards a Citizens’ Militia

Revolt Against the Age of Plenty

Hiroshima

State Intervention in Industry

These books were so familiar to me — I was then working in Mushroom Bookshop in

Nottingham — that I can remember the authors and publishers even now. Days of

Hope, by the way, produced two members of the UK Cabinet, Alan Milburn, once

Secretary of State for Health, and the late Mo Mowlam, once Secretary of State

for Northern Ireland. I wonder what they thought of their days back in a

radical bookshop known locally as Haze of Dope. Protest and Survive, which

appears on both lists, was first published in Nottingham by Spokesman Books as

a pamphlet — Mushroom Bookshop alone sold over 1,000 copies of EP Thompson’s

response to the Government’s Protect and Survive handout. It was later expanded

into a book and published by Penguin.]

It’s easy to mock radical bookshops. The comedian Alexei Sayle was once a Maoist. His group’s bookshop, Bellman Books, he wrote ‘was a dark and forbidding former bank … [in] a depressive Irish neighbourhood of gloomy pubs, grey rooming houses and cash butchers. There were at least two other Maoist bookshops in the area owned by competing sects … These other places had proper MarxistLeninist names such as the London Workers’ Bookshop, but bizarrely the Bellman was named after a character in Lewis Carroll’s nonsense poem “The Hunting of the Snark” who says, “What I tell you three times must be true” and possesses a map of the ocean which is a blank piece of paper. What sort of message was that sending?’

Up in Sheffield, following a very successful radical book fair in association with the library service attended by 1,700 people, one local (Conservative) city councillor was not happy. He wrote “I put in an appearance at the Radical Book Fair at the Town Hall. Anarchists, feminists and every conceivable variety of ragbag lefty was present peddling their wares. For my part I saw no ordinary Sheffielders, just a bunch of grimfaced souls trying to look interested in some rather dull books. Is this the right use for the Town Hall on a Saturday?” But those 1,700 people did not look grim nor found the books dull.

It was actually the Communist Party (CP) which first set up socialist bookshops in Britain in a big way. Most of those mentioned so far were libertarian, but the CP ran a number of chains, peaking in the 1940s. As well as obvious places such as Glasgow (whose Clyde Books soldiered on until 1993), they had shops in small towns in industrial areas such as Kirkcaldy in Scotland, but also conservative market towns such as King’s Lynne and Gloucester. The CP even had a mobile library at one stage. Communist material sold well, with every branch having its own lit(erature) sec(retary). Key Books in Birmingham said in 1946 in How to Sell Literature that a mass pamphlet should have a national sale of 150,000 and that in the previous five years they alone had distributed over two million pamphlets and periodicals. By modern standards much of their material would not stand up … Stalin calendars for example. Or the works of Georgi Plekhanov. And many of the writers once popular in Communist circles, such as Karl Radek, would not survive Stalin’s purges.

Here and there were shops from other traditions, anarchist or, in Nottingham, Pat Jordan’s International Bookshop, which sold an assortment of smut, secondhand popular books, and books within the Trotskyist tradition.

By the 1970s, the Communist bookshops were in terminal decline. Counterculture bookshops, not radical bookshops as such, filled some of the gap, selling avant garde literature. Strangely, I bought a number of avant garde books from an ‘adult’ bookshop (ie one specialising in pornography). These included Genet, Henry Miller and others from Aberdeen’s adult bookshop, which had the unfortunate name of ‘Willy’s’. I made a point of never going beyond the front racks. It was also the only place I knew that sold Private Eye, then banned from WH Smith. Countercultural bookshops such as Ultima Thule in Newcastle, Jim Haynes’ Paperback Bookshop in Edinburgh and Unicorn in Brighton were largely before my time, but Compendium in London (19682000) carried countercultural books, Beat material, anarchism, little magazines, feminism, spirituality and radical therapy. Whilst it was never radical as such — it was commercially owned and commercially successful — Compendium was a bridge between generations. Trent Books in Nottingham, which had similar literary tastes, lasted only a few years but imported a massive amount of American material. In 1966 it organised a large poetry festival. Every reader was male, something that would be impossible now. That shop closed in 1972. Amamus, in Blackburn, had a longer life; like Compendium, crossing the boundaries of counterculture, radical politics and feminism.

Closures have always been inevitable — Proletarian Books in Doncaster and Beautiful Stranger in Rochdale were probably doomed to failure, but people did their best. And at times it was not easy. I don’t just mean economically. The bookshop I worked in was raided by the police for stocking books on drugs, including wellknown literary works. We won the ensuing court case, with costs awarded against the police, though a couple of manuals were lost, as was the joke book A Child’s Garden of Grass which, it was thought, an unwary child might buy in place of A Child’s Garden of Verse. Others were prosecuted for selling gay books. Sometimes parcels from the USA containing lesbian and gay books simply disappeared in transit. Particular books on the war in Ireland were of interest to the police. This was before the days of the internet when it was easier to stop imports, but the state was largely unsuccessful in holding back radical bookshops. Mushroom Bookshop imported a banned title on the British intelligence services, Spycatcher, from several different countries, including the Netherlands and the USA, and filled our windows with copies. Oddly, the first person to see the window display was a policeman, who came in, advised us that the book was illegal, wished us luck and left quickly!

But often the biggest threat was from the far right. In 1826, there was a free thought (atheist) bookshop in Nottingham which was under siege by fundamentalist Christians for weeks. At one stage the owner, Susannah Wright, kept a pistol for her own protection. Her assailants were the political ancestors of the fascists who regularly attacked radical bookshops in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. A lot of the trouble from fascists was low level, gluing up locks, spraypainting windows, phoning death threats, but some of it was more physical. Shop workers were sometimes injured in attacks. In Fourth Idea Bookshop in Bradford one fascist assaulted a customer only to find out he was an undercover policeman snooping in the shop! In 1994, some 50 fascists smashed up Mushroom Bookshop. Thirteen served prison sentences for doing so. But we were also under pressure from Islamic fundamentalists over Satanic Verses. The response of the radical book trade was to sell the book openly, under posters saying ‘Fight Racism, Not Rushdie’. The fascist threat has diminished, but has not gone away. Last summer, the London bookshop Bookmarks was invaded by people from the far right. The book trade as a whole rallied to their support, including the commercial sector.

At the height of the radical book trade there was an annual Socialist Bookfair, involving some 450 publishers including those from the academic and commercial sectors, an annual Feminist Book Fortnight, several International Radical Black and Third World book festivals, a London Irish Book Festival, specialist distributors, and Booksellers’ Action for Nuclear Disarmament, which brought together bookshops, writers and publishers. The London Anarchist Bookfair was the only survivor up to modern times.

The radical book trade shrank for many reasons. Funding dried up, changes in local taxation were not favourable to small businesses, the British Net Book Agreement collapsed (which enabled the chains, then the supermarkets, then Amazon to sell books at a discount, cherrypicking the best sellers). The collectiveworking ethos of many shops struggled with changing times as city centre rents soared. Idealist young people opened cafés, not bookshops.

But, over the last few years, the radical bookshop movement has begun to find its feet again, creating a structure. We reformed as the Alliance of Radical Booksellers. The Bread and Roses Award for Radical Bookselling started up, which spawned the Little Rebels Award for radical children’s books. The London Radical Bookfair was set up and has been hugely successful, and a decentralised anarchist book festival replaced the London Anarchist Bookfair. There are local anarchist and socialist bookfairs springing up. There have been a few new openings, notably Lighthouse Bookshop in Edinburgh, but also many of the recently opened commercial shops are radical even if not formally so. This was evidenced when Five Leaves Bookshop revived the Feminist Book Fortnight last summer, with fifty bookshops taking part from across the radical and commercial sector. The general trade increasingly sees diversity (in class, race, sexuality) as important in its staffing and what is being published, which has helped to bring the radical side and the commercial side together.

News from Nowhere still flies the flag as a women’s collective, sometimes using the slogan ‘Shop with the Real Amazons’. In 2017 Housmans, London’s premier radical bookshop, won the London Independent Bookshop of the Year award and, in 2018, Five Leaves Bookshop in Nottingham became the national Independent Bookshop of the Year, the first radical to do so. Staying the course is important and, yes, that means being more businesslike, paying decent wages to retain staff, and drawing in new customers all the time. Locally, our partners include Nottingham City of Literature, a UNESCO project. Indeed, it was a member of our staff who wrote the bid that won City of Literature status. All the selfdefined radicals aim to build strong local partnerships.

In 1943, Harold Laski wrote:

‘If I had to put the purpose of this war in a sentence I would say that we fight it that men and women may freely choose themselves the books which give nourishment or pleasure. In Germany they burn the books; in Britain we sell them. So long as we can continue to say that, we can be confident of the outcome of this struggle.’

We continue to say that.

More parochially, as I write this, our bookshop’s 2018 events programme has just finished. It included an evening of translated poetry from around the world and a talk on Rojava, the liberated Kurdish area in Syria. Over previous weeks, we had evenings on the lives of Trans people, on Travelling people/Romanies, on older lesbians, discussions on Black history — forty events this autumn, and our own radical bookfair with supporting programme. I’d like to think that Susannah Wright, she who packed a pistol to defend her bookshop in 1826, would have approved.

A version of this article first appeared in the Journal of Humanity, the counterculture journal of Nieuwe Vide in Holland.